The price of petrol is anything but nebulous: Americans drive by petrol stations and refill their tanks several times a week. When prices rise or fall, they notice

for rising gross domestic product, or penalise them if it is on the low side? What about falling or rising unemployment? And what if economic signals do not all point the same way? Political scientists reckon that annual changes in GDP and employment indicators do matter—but also that many citizens simply go by the president’s rhetoric and the tone of media coverage.

Second, partisanship has come to dominate voters’ perceptions. In “Identity Crisis”, a book published in 2018 about voter psychology and behaviour in the 2016 election, three political scientists, John Sides, Michael Tesler and Lynn Vavreck, find that the University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment had predicted the approval ratings of presidents from Kennedy to George W. Bush pretty accurately. But under Barack Obama and, the correlation fell apart.

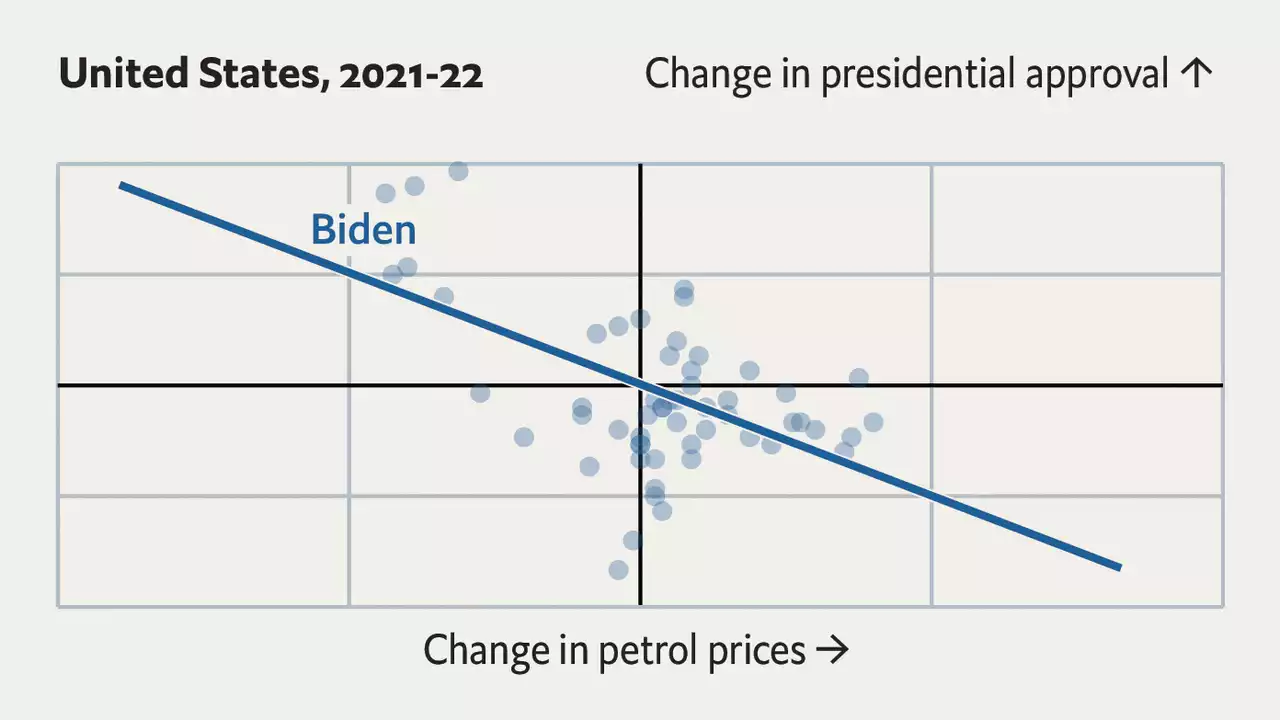

One way around both these analytical problems is to look instead at the link between petrol prices and presidential approval. . Looking at this relationship also avoids an issue that pollsters call “expressive responding”—when people answer questions in a way that makes their party look good, as they do in the University of Michigan’s economic surveys.analysis of presidential approval ratings and the price of fuel, all presidents except Donald Trump got a ratings boost when petrol prices fell .

Mr Trump’s presidency caused social scientists to speculate that mass voter psychology had entered a new, sectarian, post-rational era, in which millions of Americans had simply become unmoored from reality. That may well be so for some issues. But Mr Biden promised a return to the normal rules of politics. At least when it comes to the connection between petrol prices and presidential approval, he has kept his word.